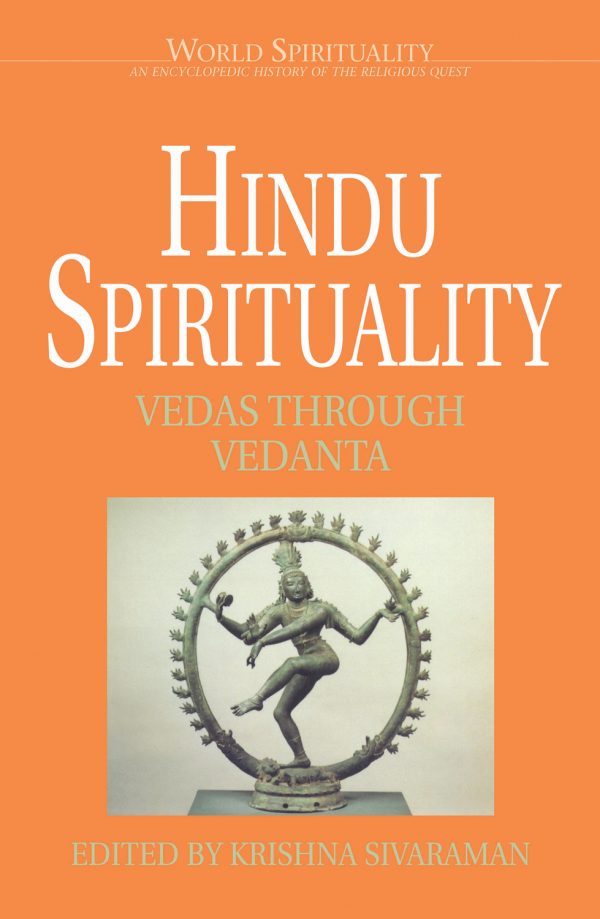

- Title: Hindu Spirituality

- Page Count: 496

- Available Formats: Trade-paper (9780824599287), Trade-paper (9780824516710)

- Edition: Trade Paper

- Original language: English

- Retail US: Trade-paper (49.95), Trade-paper (49.95)

- Retail Canada: Trade-paper (66.95), Trade-paper (59.95)

- Retail Canada: 66.95